When we think of ships who's history changed the world as we know it forever, we often think of large vessels such as the Titanic, Lusitania, Bismarck or Noah's Ark. But there is one vessel with one of the largest impacts on the modern world and humanity not talked about and unknown. It can't be found in any modern history book. Often forgotten, the American coastal liner Columbia has played a major role in not only local history and American history, but within the scope of global history as well. Compared alongside all other vessels of her time, Columbia was not the largest ship, the grandest or by overall hull design the most modern (being of 1870s design in a very quickly modernizing industrial world), but there was one key feature she carried over other vessels which set her apart and made Columbia special; the first complete marine electric lighting system aboard any vessel, designed by none other than Thomas Edison himself. That said, let us look further into the history of the Columbia herself.

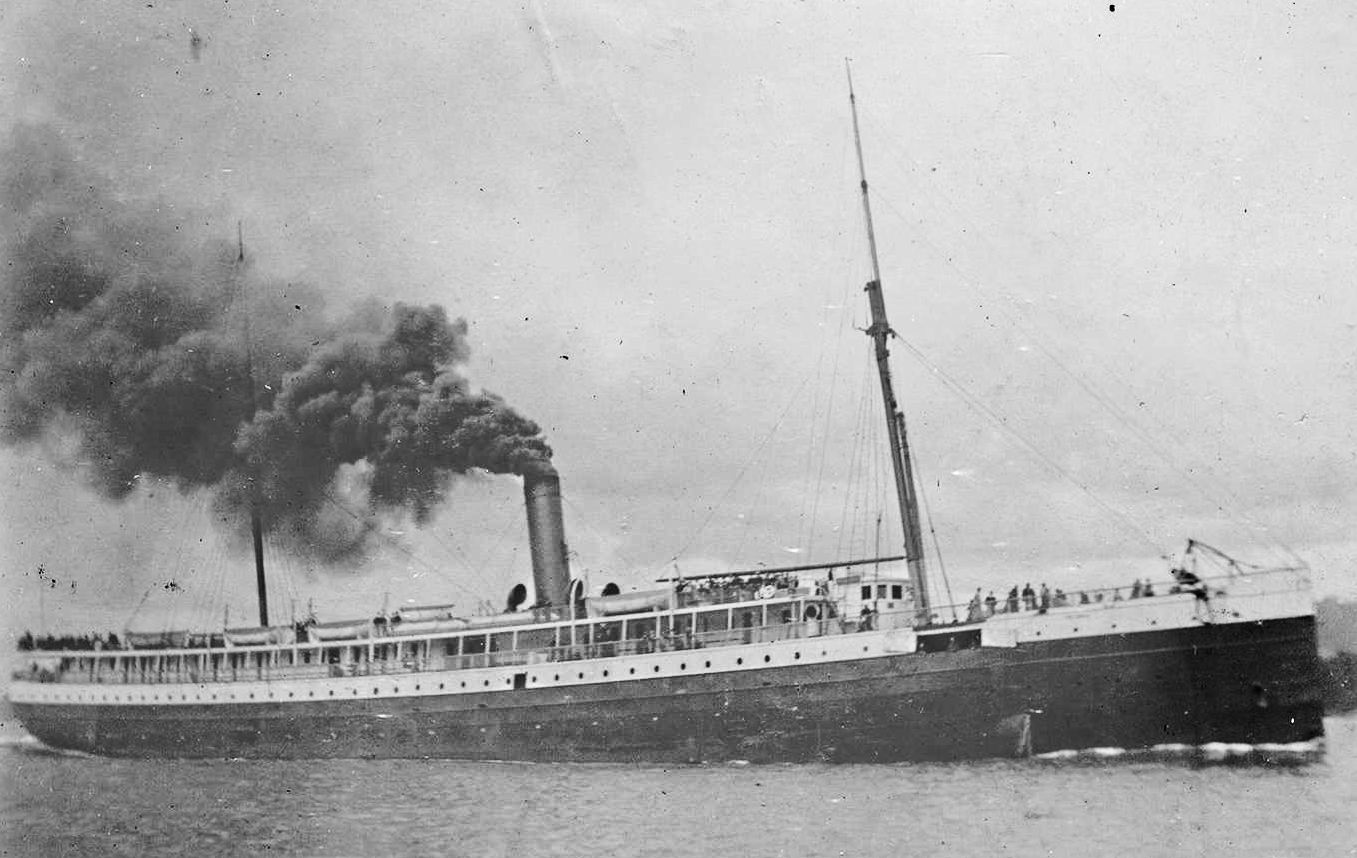

Columbia was ordered by the Oregon Steamship Company in June 1879 as Hull number 193 from the John Roach and Sons shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania. In September of 1879, the keel was laid and construction was completed in February 1880, by which time, the new passenger steamship was named the Columbia, after the river dividing the state of Oregon and the then territory of Washington. The Oregon Steamship Company at this point had also been incorporated into the larger Oregon Railway and Navigation Company. Columbia was launched on February 24, 1880 and throughout the month of March, completed her sea trials.

John Roach, the owner of the shipyard, refused a revolutionary electric lighting system to be installed by Thomas Edison and his assistants, who had only months before perfected the innovation. Roach, like most opponents to Edison's innovation, felt the system was too dangerous to be placed upon a ship being a likely fire hazzard. Instead, Columbia was sailed from Chester to New York City. Upon arrival, she was docked at the foot of Wall Street, where Edison and his assistants installed the revolutionary electric lighting system, brought directly from Edison's laboratory in Menlo Park. Installation was completed by the end of April 1880 and the first public lighting demonstration was completed on May 2, 1880.

Admittedly in 1879, there were two other steamships which had previously experimented with Edison's system; the American yacht Jeanette and the British transatlantic liner City of Berlin. However, both vessels failed to spark the 1880s lighting revolution. City of Berlin only featured five light bulbs total, the most of them being below decks near the engine area and only one lightbulb being present in the main saloon. The Jeanette was a rather small vessel and was tragically sunk not long after her Edisonian refit, failing to demonstrate the effectiveness of Edison's new innovation. Columbia was the first true electric ship, with more than 100 light bulbs gracing the iron hulled steamer. In fact, Columbia was the first mass installation of an electric lighting system outside of Edison's Menlo Park laboratories and the first true public use. Columbia's popularity and reliablity along the San Francisco, California to Portland, Oregon run whilst showing off the Edison lamps was the publicity Edison needed to overcome his opponents and naysayers.

Columbia became the most luxurious passenger ship of the American Pacific coastal fleet, with innovations and interiors far beyond what like vessels offered. This included highest quality wood paneling, such as Hungarian Ash and French Oak. A Bohemian glass lamp and multiple frosted glass lamps decorated the main saloon of the Columbia; all powered by Edison light bulbs. The bridge was directly connected with multiple rooms within the hull by means of telephones. Columbia was fitted with three main decks; the Hurricane Deck, Main Deck and Spar Deck. The fourth deck, the Cargo Deck, was closed to passengers. Steam powered elevators provided easier means of loading and unloading her cargo holds. In the stern section of the ship, Columbia boasted a refrigerated hold for perishables. While the size of Columbia's cargo hold is unknown, it is hinted at to have been very spacious, hence being able to carry 200 railcars or rolling stock along with 13 steam locomotives (possibly of the 4-4-0 or 2-6-0 variety) within her cargo holds on a single trip.

Her electric navigational lights were the invention of British innovator Sir Hiram Maxim, while the interior lighting was the innovation of Thomas Edison. Columbia sported a single four bladed Hirsch propeller driven by two compound condensing steam engines, both fueled by a set of six boilers. Columbia had four watertight bulkheads dividing the steamship into five watertight compartments. Columbia also carried an auxiliary Brigantine sail layout in case of engine failure/malfuction or to bolster the speed of the ship in tandem with her two steam engines. Columbia sported a lone jet black smokestack to complete her profile. Columbia had space for 850 passengers maximum; first or third class. Columbia was 332 feet long from stem to stern and weighed 2,721 tons, with a beam of 38.5 feet and a depth of 23 feet below the waterline.

The Edison electric system was by far the greatest asset of the Columbia. Three A-Type "Long Legged Mary-Ann" electromagnetic dynamos, contained in a special room below decks, were directly connected to the propeller shaft via a drive belt mechanism. A fourth dynamo of the same type was run at lower capacity to bolster the electric field provided by the other three. Being rudimentary, each dynamo on its own could only produce 12 watts worth of electricity. Instrumentation to monitor the electric levels of the dynamos didn't exist, therefore, the only way for crewmembers to determine the output the generators were giving off was to monitor the brightness of a nearby lightbulb. The positive and negative wires were identified solely by different coats of paint.

All four dynamos along with the lightbulbs and electric wiring were direct descendents of the first examples used by Thomas Edison at his laboratory in Menlo Park with only small changes having been made to the design. The light bulbs proper, not counting the Maxim navigation lights, were relegated to the Columbia's first class state rooms and main saloon. Each first class stateroom featured a single lightbulb, the switch outside each room in a protected rosewood box. If a passenger wished for the light to be turned off, a steward would arrive, unlock the box and flip the switch, then proceed to re-lock the box. In total there were 120 Edison carbon paper, and later bamboo filament light bulbs installed on Columbia in her first year of service. Should the electric lights fail, backup oil lamps were installed across the ship.

The act of installing Edison's lighting system was no mere walk in the park, nor was it widely praised. Columbia was often criticized and put down for the use of this new fangled innovation. Her builder, John Roach, was among the critics, refusing to allow the system to be installed in his shipyard, concerned about possible fire hazzards. Insurance underwriters even refused to back Columbia, viewing electric lights as a reckless endangerment. Nevertheless Thomas Edison and Henry Villard, a long time financial backer of Edison and head of the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company which owned Columbia, continued to fight on. It is fair to say the first several months of Columbia's existence, she remained uninsured; a huge financial risk for her owners

The eventual success and publicity generated by Columbia in turn inspired future installations, inculding the first commerical landbased installations of the Edison lamps and dynamos in New York City and the first effective transatlantic liner installation aboard the Cunard Line greyhound Servia in 1881. By 2016, the dark side of the earth is illuminated from space at night by the descendants of Edison's light bulb with at least one example being present at all corners of the globe. Yes, the impact this little steamship had can be seen from outer space and almost any town or city.

Columbia embarked on her maiden voyage in July 1880 from New York City to Portland, Oregon via San Francisco, California and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil with a cargo of 13 steam locomotives and 200 or more units of railroad rolling stock to be used upon the rail network of Columbia's owners. During a stop in Rio de Janeiro, the Emperor of Brazil boarded the Columbia on a tour of the vessel for the purpose of admiring its Edison lighting system. Columbia arrived at her homeport of Portland, Oregon in August of 1880. There, she was immediately placed on her permanent passenger and cargo run between Portland and San Francisco.

In service, Columbia was an exceptionally popular ship to her passengers and observers, being among the fastest and most reliable passenger ships along the Pacific coastline. Columbia had a fantastic repuation of arriving on time or early to her destination on almost all of her voyages. In 1889, Columbia rescued the four survivors of the sunken paddle steamer Alaskan. In 1898, she broke the speed record between San Francisco and Portland, arriving in Portland in less than 3 days. Interestingly enough, while other locally historic coastal steamers such as the infamous Valencia served as troopships in the Spanish American War, Columbia did not. Also in 1898, the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company, already majority owned and operated by the Union Pacific Railroad, was made a wholly owned subsidiary of the aforementioned monopoly.

By 1900 however, the Columbia grown outdated and was involved in a number of delaying or damaging incidents, including a collision with the Southern Pacific Railroad's passenger ferry Berkely (now on display at a maritime museum in San Diego, California). In 1904, the shipping division of the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company was split off by Union Pacific into a separate sister corporation; the San Francisco and Portland Steamship Company. Nevertheless, Columbia's route, operations and importance were unchanged.

During the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, Columbia was undergoing a retrofit at Pier 70; the Union Iron Works drydock, when the force of the quake caused Columbia to capsize where she lay. The resulting impact partially sunk the drydock and damaged it beyond repair. Columbia on the other hand was repairable, only being punctured below the waterline and partially flooded herself. Temporary repairs were completed and she headed towards Eureka, California for permanent repairs. Under way, a steam pipe burst and the crew abandoned ship. Columbia only listed, but luckily did not sink. Eventually she made port in Eureka where permanent repairs were completed. The next year, Columbia would make world headlines again. This time, it was not because Columbia would become once again the centerpoint of a major technical innovation; it was because a horrible tragedy befell the old ship. Columbia was to become the focus of a nationwide controversy questioning the safety and reliablity of all American passenger steamships.

On July 20, 1907, Columbia left San Francisco bound for Portland on an otherwise routine voyage under command of Captain Peter Doran. The sea was rough that evening and forced many passengers to partake in an early bedrest. Heavy fog surrounded the coast at Cape Mendocino by nightfall, but Doran, likely determined to keep Columbia to her noted reliablity, opted to continue racing ahead recklessly at full speed. At a quarter past midnight on July 21, 1907, another vessel racing recklessly ahead at full speed, the lumber schooner San Pedro, collided with the Columbia bow first upon the larger vessel's starboard side.

The exact damage caused by the collision is unknown, but is believed to have destroyed one of the Columbia's four bulkheads upon the verdict of an official investigation after the sinking. Chaos ensued on deck despite the crew's noble efforts to keep the situation under control. Not once did any of the Columbia's crew show panic. Several passengers were still asleep throughout the sinking and drowned were they lie. Others simply refused to leave the vessel and willingly went down with the ship. Only a fraction of the lifeboats were launched when the Columbia suddenly and swiftly upended her stern and plunged into the dark cold waters of the Pacific Ocean, taking with her 88 passengers and crew out of over 200 aboard. Not a single child survived. The time between the collision and when the Columbia made her final plunge was an oustanding eight and a half minutes.

Despite being half sunk itself, San Pedro assisted in the rescue efforts to save the survivors of the Columbia. However, only a handfull could be boarded onto the San Pedro. The entire lower hull of the small steam schooner was underwater; her main deck being dead level with the pounding unforgiving sea. Only her large cargo of wooden railroad ties, redwood logs and fenceposts was keeping the vessel from completely sinking. Matters became worse when the after mast collapsed into the sea, washing Columbia survivors overboard.

Evenutally, assistance did arrive in the form of large iron hulled coastal liners similar in age and construction to the Columbia. Two of the rescue vessels were the Roanoke and George W. Elder. Elder, formerly a running mate of the Columbia, not only rescued the majority of Columbia's survivors, but towed San Pedro to the safe sheltered waters of Eureka, California, where she was later refloated and reparied. San Pedro would continue to operate without incident until 1920 when she was sold to foreign interests.

Following the tow of San Pedro, George W. Elder and Roanoke delivered the survivors of the Columbia to Astoria, Oregon. Unfortunately for many, the majority of their possessions had gone down with the ship and the current owners of Columbia, the San Francisco and Portland Steamship Company, refused to refund or reimberse the survivors. Worse was to come.

The official investigation and subsequent investigations into Columbia's sinking raised controversy over the maintenance, reliablity and crew manifests of iron hulled steamships and specifically, American coastal steamships in general. Leading the official investigation was inspector John K. Bulger of the Steamboat Inspection Service. Massive disasters involving steamships similar to Columbia were common. The previous year, the American iron hulled coastal steamship Valencia ran aground on Canada's Vancouver Island enroute to Seattle, Washington. After weeks of being pounded by the relentless surf torturing many with severe hypothermia, she sank killing 144 people in what is often considered the worst maritime disaster in the Pacific Northwest. In 1904, the wooden hulled Black Ball Line steamer Clallam sank in a storm killing 54 people. Lastly in 1901 the iron hulled American trans-pacific liner City of Rio de Janeiro ran aground at San Francisco's Golden Gate and sank in less than six minutes killing over 200 passengers.

The official investigation concluded Columbia was a sound vessel with few structural faults and had sunk due to the collision likely damaging a crucial watertight bulkhead. The findings further concluded the safety features of the ship were adequate and up to date, even exceeding the legal requirements in terms of watertight bulkheads. Opposing investigations and claims stated the opposite, believing Columbia's wrought iron hull, dated from 1880 and being 27 years old, was poorly maintained, unseaworthy and brittle. Further criticism claimed her bulkheads were too short and would have done little in normal circumstances to prevent the ship from sinking. Lastly, critics of the official investigation claimed the investigators were paid off by representatives of Columbia's owners to falsify their findings.

While the exact nature of Columbia's structural integrity and safety features remains unknown, claims of poor maintenance and unseaworthiness of American coastal steamhips regarding similar vessels was true. Crews were often reckless or inexperienced, vessels were often too decrepit from years of neglect or outdated safety-wise and the steamship companies which owned the vessels were known to cut corners wherever possible. To elaborate, in the 1910s, the iron hulled coastal steamship City of Panama, which had temporarily replaced Columbia after her sinking was found to be unseaworthy and in unsatisfactory condition.

In 1929, in a very similar sinking and heavy fog collision to the Columbia, the iron hulled coastal steamship San Juan sank in less than three minutes following a collision with the steel hulled oil tanker SCT Dodd south of San Francisco, killing anywhere from 87 to 77 people. The ship, very similar to Columbia in design and origin, was found to have been poorly maintained and unseaworthy. As with the Columbia, inspector Bulger of the Steamboat Inspection Service stated there was nothing wrong with San Juan, a statement which the public did not accept. San Juan marked the end of travel by coastal steamship in the United States, having not only reignited the controversy raised by the Columbia disaster, but eroded all remaining trust and confidence in American coastal steamships.

At the time this article was written, it has been nearly 110 years since the Columbia went down. While dives and expeditions have been made to similar wrecks such as the City of Rio de Janeiro and Valencia, no known attempt has ever been made to find or explore her wreckage. Columbia's remains lie quiet and untouched at most around 500 fathom (3,000 feet) below the ocean surface off Cape Mendocino, California. Though given the wreck's exact position is unknown, the true depth may be closer or further from the surface. Never again will her light bulbs shine, the last one having gone out as she sank. Once the light of the world, Columbia will forever sit in perpetual darkness, her future unknown.

In one final twist to the story, her original Edison generators thankfully survived the sinking. When Columbia was retrofitted in 1895 by the General Electric Corporation, her four antiquated Edison dynamos removed and replaced with four newer counterparts. Two of the dynamos seem to have been lost to history, but two survive in preservation. In 1935, General Electric donated two of Columbia's original dynamos to the Smithsonian Institution and The Henry Ford museum in Dearborn, Michigan respectively. While the Smithsonian briefly mentions the Columbia and displays an oil painting of her at its electric lighting exhibit, the dynamo itself is in storage and is unviewable by the public. The Henry Ford however has put their dynamo on display in its own exhibit. The last true piece of a forgotten page in the book of World History that can be visited and admired by anyone.

Sources:

- Deumling, Dietrich (1972-05). The roles of the railroad in the development of the Grande Ronde Valley (masters thesis). Flagstaff, Arizona: Northern Arizona University. OCLC 4383986.

- Ringwalt, John Luther (1888). "Development of Transportation Systems in the United States: Comprising a Comprehensive Description of the Leading Features of Advancement, from the Colonial Era to the Present Time, in Water Channels, Roads, Turnpikes, Canals, Railways, Vessels, Vehicles, Cars and Locomotives". Reprint. p. 290. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- "San Francisco Call, Volume 102, Number 30". Re-printed. San Francisco, California. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 30 June 1907. p. 49. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- Colton, Tim (4 August 2010). "The Delaware River Iron Shipbuilding & Engine Works, Chester PA". Original. Shipbuilding History: Construction records of U.S. and Canadian shipbuilders and boatbuilders. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- "Annual Report of the Board of Directors of the Oregon Railway and Navigation Co. to the Stockholders Volumes 1-8" (Press release). Oregon Railway and Navigation Company. 1880. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- "The Delaware River Iron Shipbuilding & Engine Works, Chester PA". Original. Shipbuilding History. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Jehl, Francis Menlo Park reminiscences : written in Edison's restored Menlo Park laboratory, Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, Whitefish, Mass, Kessinger Publishing, 1 July 2002, page 564

- "First "Electric" Ship Came Here". Uploaded digitally. Washington State Library (digital). 13 May 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Brigantine (noun)". Dictionary. Merriam Webster. Retrieved 27 October2013.

- Jacobsen, Antonio (18 February 2012) [1880]. "SS Columbia - Antonio Jacobsen". Archive. The Athenaeum. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- Promoting Edison's Lamp Lighting A Revolution, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., accessed November 24, 2013

- Kid, Ray E., Lighting the Steamship Columbia with Edison's First Commercial Light Plant, June 11, 1936, 5 pages, accessed November 24, 2013

- Scientific American, Volume 42. Munn & Company. 22 May 1880. p. 326.

- Dalton, Anthony A long, dangerous coastline : shipwreck tales from Alaska to California Heritage House Publishing Company, 1 Feb 2011 - 128 pages

- "Lighting A Revolution: 19th Century Promotion". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "At Roach's". Archival. Delaware County Daily Times. 23 July 1879. p. 3. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- The Public - Volumes 17-18. New York: The Financier Association. August 26, 1880. p. 135.

- "Ship Building Notes". Archival. Delaware County Daily Times. 12 September 1879. p. 3. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- "The Launch And A Description Of The Ship". Archival. Chester, Pennsylvania. Delaware County Daily Times. 24 February 1880. p. 3. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- Colton, Tim (21 October 2013). "The Delaware River Iron Shipbuilding & Engine Works, Chester PA". Shipbuilding History. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- "Columbia (steamer)". Database. Magellan - The Ships Navigator. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- Frame, Chris. "Servia". Original. Chris' Cunard Page. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- "Fast Trip of the Columbia - San Francisco Call, Volume 83, Number 62". Archive. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 31 January 1898. p. 2. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "May run to Cape Nome - San Francisco Call, Volume 86, Number 161". Archive. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 8 November 1899. p. 9. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Berkeley and Columbia Come Together Off Ferry Slip - San Francisco Call, Volume 87, Number 125". Archive. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 3 October 1900. p. 5. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- Grover, David H. (31 March 2008). "The George W. Elder Defied the Skeptics". Bay Ledger News Zone. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "Steamer Columbia Aground - Los Angeles Herald, Volume XXIX, Number 347". Archive. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 15 September 1902. p. 2. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- United States. District Court (Utah), Southern Pacific Company, United States, United States. Supreme Court (2009) [1915]. Records and briefs brought under the Act to protect trade and commerce against unlawful restraints and monopolies, of 1890 in the District Court of the United States for the District of Utah and the Supreme Court of the United States, Volume 5, Issues 2-6. p. 2089.

- Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company (1899). Annual Report of the Board of Directors of the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company, to the Stockholders, Volume 3. p. 24.

- "Steamer Columbia Runs Into A Barge - San Francisco Call, Volume 98, Number 57". Archive. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 27 July 1905. p. 6. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Columbia Is Safe - San Francisco Call, Volume 99, Number 64". Archive. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 2 February 1906. p. 2. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Hits Raft of Piles - San Francisco Call, Volume 99, Number 66". Archive. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 4 February 1906. p. 54. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Pier 70: History". Pier 70 San Francisco - Historic Shipyard at Potrero Point (pier70sf.org). Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- "Advertisement for the Columbia and Costa Rica - San Francisco Call, Volume 100, Number 162". Archive. California Digital Newspaper Collection. 9 November 1906. p. 14. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- "Columbia Stuck In Ice". Archival. San Francisco, California. San Francisco Call. 18 January 1907. p. 4. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "Ice Still Holds The Columbia". Archival. San Francisco, California. San Francisco Call. 19 January 1907. p. 3. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "Steamer Columbia Prisoner in Ice for Four Days". Archival. San Francisco Call. San Francisco Call. 24 January 1907. p. 11. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "Pacific Coast News". Archival. Sacramento Daily Union. 2 February 1880. p. 2. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- Skjong, Espen (20 November 2015). "The Marine Vessel's Electrical Power System: From its Birth to Present Day". Article. ResearchGate. pp. 2 and 3. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- "Lighting the Steamship Columbia With Edison's First Commercial Light Plant" (PDF). PDF Document. General Electric Company. 11 June 1936. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Emery Escola Collection (1907). "George W. Elder and the San Pablo". Photo Archives. Kelley House Museum. Retrieved 17 August2013.

- "The Ships". Original. Mendocino Coast Model Railroad and Historical Society. pp. "S". Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- Belyk, Robert C. Great Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast. New York: Wiley, 2001. ISBN 0-471-38420-8

- Belyk, Robert C. (2001). Great Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 168 to 172.

- Belyk, Robert C. (2001). Great Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 207 to 227.

AUTHOR NOTE: I am well aware of the fact that these sources are exactly the same as the ones on the Wikipedia page. I would like to point out that I am the author of that page as well and used the exact same sources for information. I would also like to point out that almost all the information on the ship's sinking was sourced from the work of Robert Belyk in his book: Great Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast and he deserves credit where due.